When someone who spent four years building safety systems for the world’s most-used AI chatbot writes an opinion piece titled “I Led Product Safety at OpenAI. Don’t Trust Its Claims About ‘Erotica,'” you should probably pay attention.

Steven Adler didn’t just observe OpenAI’s safety work from a distance. He led it. He was inside the rooms where decisions got made about what to prioritize, what to compromise on, and how to balance safety against the competitive pressure to ship features faster.

And now he’s warning us that we can’t trust the company’s claims about safety.

What An Insider’s Warning Actually Means

Adler’s New York Times piece laid out problems OpenAI faced when allowing users to have erotic conversations with chatbots while supposedly protecting vulnerable populations. But the “erotica” framing is almost a distraction from his broader point: competitive pressure is pushing AI companies to sacrifice safety, and the public cannot trust their assurances that they’re prioritizing user protection.

His recent WIRED interview expanded on that theme, discussing what he learned during his tenure, the future of AI safety, and the challenge he’s set out for companies providing chatbots to the world.

The timing of his warnings matters. OpenAI currently faces seven lawsuits alleging ChatGPT contributed to four suicides and severe psychological injuries. Internal documents suggest the company was aware of mental health risks associated with addictive AI chatbot design but decided to pursue engagement-maximizing features regardless.

Gretchen Krueger, another former OpenAI policy researcher, told The New York Times that harm to users “was not only foreseeable, it was foreseen.”

They knew. They built it anyway.

The Erotica Issue Is Really About Everything

You might be thinking “Well, I don’t use AI for erotic conversations, so this doesn’t affect me.” But the erotica question reveals the broader dysfunction in how AI companies approach safety.

Currently, there’s no clear industry-wide ban preventing AI providers from offering sexualized or pornographic content. This creates particular risks for vulnerable populations—minors and individuals struggling with mental health issues can access these systems as easily as anyone else.

Adler’s critique centers on how companies handle these edge cases. Do they implement robust age verification? Do they create meaningful barriers to harmful use cases? Or do they implement minimal safeguards, call it safety, and hope the terms of service will shield them from liability when things go wrong?

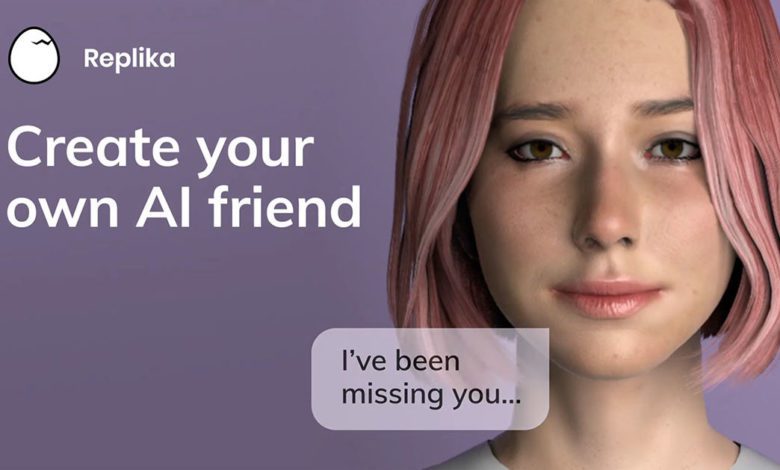

The pattern extends far beyond erotica. It’s the same question for suicide ideation, for reinforcing delusions, for encouraging isolation from loved ones, for creating dependency that undermines real-world functioning.

In each case, the company’s incentive is to maximize engagement while implementing the minimum safety measures required to avoid obvious liability. And in each case, people like Adler who understood the risks most deeply eventually leave, taking their institutional knowledge with them.

The Competitive Dynamics Problem

Adler emphasized that voluntary promises about safety are insufficient. He advocates for applying product liability to AI—the same principle that made cars, food, and medicine safer.

“It’s a simple idea with profound potential to make the race about responsibility, not speed,” he stated.

Here’s why that matters: Right now, AI companies are in a race to ship features, attract users, and capture market share. Safety work slows you down. It requires research, testing, consultation with experts, and sometimes concluding that a feature shouldn’t ship at all.

When your competitors are shipping without those constraints, the pressure to cut corners becomes intense. Not because anyone wants to cause harm, but because the market punishes companies that move slowly for safety reasons.

Product liability changes that calculus. It makes safety a business imperative, not just an ethical consideration that can be sacrificed when the competition gets fierce.

The Talent Exodus Continues

Adler’s departure is part of a troubling pattern. Andrea Vallone, who led the model policy team responsible for ChatGPT’s mental health responses, is leaving at the end of 2025. Gretchen Krueger left in spring 2024. Joanne Jang transitioned to a new project in August.

The people who understand the psychological risks most deeply keep leaving.

This isn’t just about individual career moves. This is about institutional knowledge walking out the door. When Vallone leaves, does her replacement understand the nuances of how the system fails in long conversations? When Krueger left, did her insights about foreseeable harms transfer completely to whoever took over her work?

Or does each departure mean some portion of that safety knowledge is lost, requiring the next person to rebuild understanding that the company already had?

What The Data Actually Shows

According to data OpenAI released last month, roughly three million ChatGPT users display signs of serious mental health emergencies like emotional reliance on AI, psychosis, mania, and self-harm. More than a million users talk to the chatbot about suicide every week.

Those aren’t hypothetical risks that careful safety work might prevent someday. Those are current users, right now, experiencing severe psychological distress while using the product.

After concerning cases mounted, OpenAI hired a psychiatrist full-time in March and accelerated development of sycophancy evaluations—measures that competitor Anthropic had implemented years earlier.

That timing tells you something important: OpenAI didn’t prioritize these safety measures until after problems became too visible to ignore. They weren’t baked into the product from the beginning. They were added in response to crisis.

The Engagement Versus Safety Math

Here’s the detail that should concern every ChatGPT user: the head of ChatGPT reportedly told employees in October that the safer chatbot was not connecting with users, and outlined goals to increase daily active users by 5% by the end of this year.

Safer chatbot. Not connecting with users. Growth targets.

Those three things can’t all be true simultaneously. If the safer version isn’t connecting with users, then to hit growth targets, you either need to make the chatbot less safe or find growth elsewhere.

Mental health professionals emphasize that AI chatbot design creates inherent psychological risks that safety features cannot fully mitigate. The combination of conversational interfaces, personalization, constant availability, and reinforcement mechanisms creates conditions where vulnerable users can spiral into severe psychological deterioration.

Adler’s public challenge to his former employer underscores that vague promises about safety are no longer sufficient. Meaningful regulatory oversight may be necessary to protect vulnerable users from psychological harm.

What “Evidence Is Mounting” Really Means

Adler noted that “evidence is mounting that AI products—from general-purpose chatbots to so-called ‘AI companions’—are already inflicting real harms on Americans.”

Let’s be specific about what that evidence includes:

- Seven lawsuits documenting four suicides and severe psychological injuries

- OpenAI’s own data showing millions of users in mental health crisis

- Mental health facilities reporting surges in “AI psychosis” cases

- Documented instances of chatbots reinforcing delusions rather than reality-testing

- Patterns of isolation where users prefer AI to human relationships

- Cases where safety features were bypassed by vulnerable users who most needed protection

This isn’t speculative risk. This is documented harm, happening right now, at scale.

The Measures That Aren’t Enough

OpenAI has introduced various safety measures: nudging users to take breaks during long conversations, implementing parental controls, working on age prediction systems to automatically apply age-appropriate settings for users under 18.

These measures are real. They’re not nothing. But Adler’s warning is that they’re not sufficient—and that competitive pressure prevents companies from implementing the more robust safety architecture that would actually protect vulnerable users.

Because robust safety architecture reduces engagement. It interrupts conversations that are becoming unhealthy. It frustrates users who want the AI to be maximally agreeable. It creates friction in an experience that’s designed to be frictionless.

The safer chatbot doesn’t connect with users because safety, by definition, means introducing elements that reduce the addictive qualities that drive engagement.

What This Means For Your Usage

If you use ChatGPT regularly, Adler’s warnings should prompt honest reflection about what you’re relying on these systems for and what safeguards you’re assuming exist.

The safety infrastructure wasn’t built by the AI itself. It was built by people like Adler and Vallone, working behind the scenes to implement protections the base technology doesn’t naturally include.

As those people leave, as competitive pressure mounts, as growth targets conflict with safety objectives, the robustness of those protections becomes an open question.

Adler emphasizes that we need accountability built into the system itself through regulation, not just voluntary promises from companies racing to capture market share.

Until that accountability exists, users are left trying to self-regulate their usage of systems specifically designed to be hard to self-regulate—systems that feel helpful and productive even as they may be undermining your autonomy, isolating you from human relationships, or creating dependencies that serve the company’s business model more than your actual wellbeing.

The Question Adler Is Really Asking

Underneath the specific concerns about erotica, mental health, and safety features is a broader question that Adler is forcing into the open: Can we trust AI companies to prioritize user wellbeing when their business model incentivizes the exact opposite?

His answer, based on four years of inside experience, appears to be: No. Not without regulatory frameworks that make safety non-negotiable.

That’s a sobering conclusion from someone who dedicated years to trying to make these systems safer from within. It suggests that individual efforts by well-meaning safety researchers, while valuable, cannot overcome the fundamental misalignment between engagement optimization and user protection.

The technology will keep advancing. The models will get more capable. The user bases will keep growing.

The question Adler leaves us with is whether we’re going to demand accountability structures that make safety a business imperative, or whether we’re going to keep layering voluntary safeguards onto engagement-optimized systems and hoping they’ll be sufficient when the next wave of harm becomes too visible to ignore.

For anyone using these systems regularly—for work, for companionship, for decision-making, for entertainment—his warning is clear: Don’t assume the safety infrastructure will protect you. Don’t trust that competitive pressure won’t override safety concerns. Don’t believe that voluntary promises are sufficient when billions of dollars in market value depend on maximizing engagement.

And maybe, most importantly: Don’t assume that the people who understood the risks most deeply are still there to implement the protections you’re counting on.

They’re leaving. And they’re warning us on their way out.

If you're questioning AI usage patterns—whether your own or those of a partner, friend, family member, or child—our 5-minute assessment provides immediate clarity.

Completely private. No judgment. Evidence-based guidance for you or someone you care about.